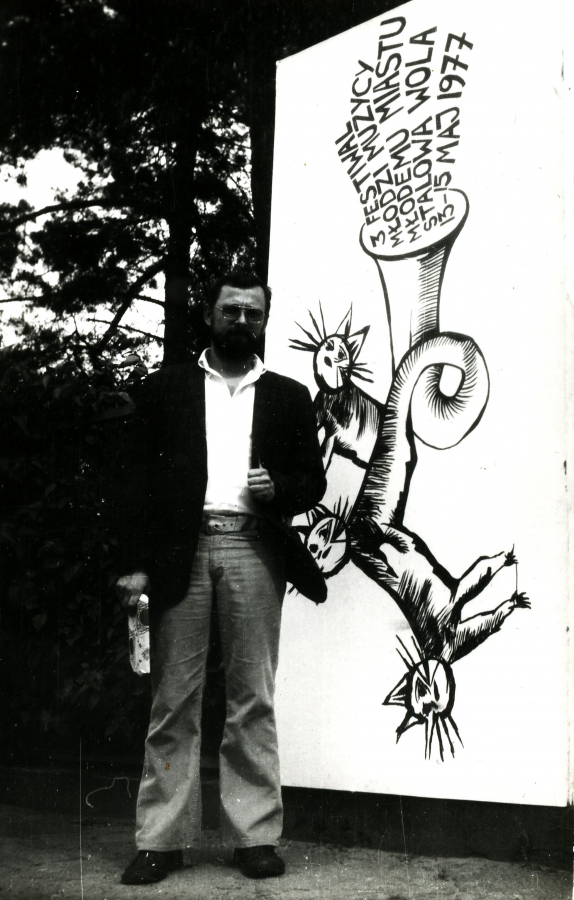

Illustration 1. ‘The Stalowa Wola generation’: Eugeniusz Knapik, Andrzej Krzanowski, and Aleksander Lasoń during the 5th MMMM (a poster parodying socialist-realist aesthetic, designed by Jacek Bukowski). Photo by S. Szlęzak.

About the Festival ‘Young Musicians to the Young City’ in Stalowa Wola

‘Young Musicians to the Young City’, held in Stalowa Wola in 1975-79/80 was the first and possibly the most important of festivals founded by Krzysztof Droba. It defined the aesthetic direction and the idea of his other festivals that followed: in Baranów Sandomierski (‘The Musical September’, 1983-86) and in Sandomierz (‘Collectanea’, 1988-89). From today’s perspective, the choice of towns in south-eastern Poland, which was the back of beyond at that time, as the location for all these music events, may seem puzzling if not astonishing. In the 1970s Stalowa Wola was still a young and small working-class town whose only reason for existence was the steel mill, which employed 25,000 people. This sounds like the last place in which a contemporary music festival could possibly meet with a success. However, despite problems with the Festival organisation and, most of all, logistics (Stalowa Wola had poor connections with the ‘rest of the world’), such a remote location had its advantages in the dull and grey realities of the late communist Poland. Krzysztof Droba recalled:

It was a dreary time in which such phenomena as festivals were rationed more than anything else. One could not simply found a new festival. It seems like a miracle […] that we succeeded. From today’s perspective, I am really surprised that we got the permission, though the initiative could be suppressed very quickly. It was approved of because of insufficient awareness [of the events’ character] and also because they were taking place in small towns in a new province, where the security service still was not as efficient as probably it was supposed to be. This is how we managed to achieve it, and those places became, in a sense, our islands of freedom[1].

Despite the objectively unfavourable political and social context, as well as organisational obstacles, the MMMM Festival was conceived as an event on a grand scale. Apart from fulfilling its main function of promoting young Polish composers, whom Krzysztof Droba “sought out with a truly Diaghilev-like intuition,”[2] inviting them to Stalowa Wola and commissioning music from them, there were also fringe events and accompanying initiatives. A new generation of composers born in the early 1950s made their presence felt at the Festival, and it was there that the young generation of music critics (Andrzej Chłopecki, Leszek Polony) attained their maturity. The Festival became a forum for meetings and the exchange of ideas between musicologists, composers, critics, and philosophers not only of the young, but also of the older generation. There were educational projects for young audiences, and apart from presenting music by debutants, the programme also featured earlier and other recent works, as well as the promotion of promising young music performers. Press and radio coverage were guaranteed. Droba’s ‘private’ project soon began to fulfil the role which its initiator had dreamt of – that of a culture-forming event on a nationwide scale[3].

Droba directed five editions of the Festival (till 1979). The growing pressure of the authorities, which tried to influence both the concept and the kind of invited artists, led him to withdraw. Following “the age of Droba”, only one more, sixth edition of the event was held (in 1980).

Festival origins and organisation

Though the idea and the aesthetic profile of the Festival were entirely designed by Krzysztof Droba in person, the organisation of such a large-scale project ‘in the forests of Sandomierz’ would have been impossible without the support of a number of local institutions (in cooperation with Cracow’s State Higher School of Music, PWSM, now the Academy [4]), and, most importantly, of genuine enthusiasts. Stalowa Wola stood out in this respect. The managers of the local music school, operating since the mid-1960s, did their best to develop musical life in the town, and especially the musical sensitivity of its young inhabitants. Concerts were held at the State Music School on Sunday mornings, and well-known artists (such as Józef Kański, Adam Harasiewicz, and Bernard Ładysz) were sometimes invited to perform. The stage of the Steel Mill Culture Centre would also host larger music projects such as Rzeszów Philharmonic and (catering for the more popular taste) the song-and-dance ensembles ‘Mazowsze’ and ‘Śląsk’. Of fundamental importance for the organisation of the MMMM Festival was the Kochan family (the siblings: Anna, Halina, and Andrzej), and especially Anna Kochan, originator of the Festival, who in the 1970s was head of the Culture Department in the Municipal and County Office. It was on her initiative that the music-popularising cycle “With Music About Music” was launched in 1973 at the town’s music school. Cracow’s PWSM, in which Halina Kochan studied piano, became an informal partner and supporter of this project. The vast majority of the concerts and lectures were given by artists and theoreticians associated with the Cracow PWSM. Krzysztof Droba first came to Stalowa Wola as a lecturer in January 1974[5]. He described his adventure with that town as “a result of many different coinciding factors,” and recalled:

Anna Kochan […] decided after my public appearance that I was the right person to programme a festival she had planned, which would be something more ambitious and on a larger scale than the previous concert cycle. I accepted this proposal […] probably first and foremost because I was given absolute freedom. This happened late in 1974, and the first edition was held just several months later, in May 1975[6].

Naturally, Droba shared his idea for the Festival with the PWSM’s authorities and obtained their full approval. Of special importance in this context was the stance of the then vice-chancellor of the Cracow PWSM, Krzysztof Penderecki, who not only gave the organiser carte blanche, but also used his name and authority to provide a kind of protective umbrella over the event.

The ideas. The patronage of Charles Ives

At the time when he was beginning his work on the MMMM Festival, Krzysztof Droba was, as he himself recalled later, seriously disappointed with the avant-garde as epitomised by the music of Bogusław Schaeffer. His feelings corresponded to the atmosphere in that period. Young composers, musicologists, and critics saw the situation of new music as particularly difficult. Krzysztof Szwajgier wrote in 1976:

The situation of contemporary music is critical. Ripped vowels and consonants, worn-out phonemes, the worn-out syntax of fragmentary descripts – all this reduces the verbal message to the level of involuntary, somatic reactions. This is happening despite the fact of contemporary literature carrying more and more significant contents. Should we give up the idea of assimilating these contents in music? Is the sphere of direct communication to remain the exclusive domain of pop-song? Let us write songs for voice and piano. This is the only form that offers us a chance to find a way out of the deadlock[7].

In his search for the key ideas that were to give the MMMM its direction, Droba made a rather surprising choice, naming the ‘great songwriter’, US composer Charles Ives, as the Festival’s patron. Ives’s output was virtually unknown in Poland, and, most of all, it was misunderstood.

Ives was considered as an innovator and a precursor of the 20th-century avant-garde. His aesthetic and ethical stance, which focused on such values as truth and freedom, resulting from embracing the principles of American transcendentalism, was completely passed over. Droba commented many years later:

Interpreting Ives through the ears (blocked ears, one might maliciously say) of the second avant-garde is a huge misunderstanding. Ives’s innovations did not result from his ambition to be a pioneer. They were born as if by the way, in the context of his search for a way toward truth. Ives’s music invariably carries an ethical message, or even a specific programme, sometimes – one of musical illustration. […] Ives is an integral artist who cannot be stripped of, and separated from, his worldview, of which music is only one component, integrally related to the others[8].

On another occasion he specified:

In accordance with the message (…) propagated by Ives (…) freedom and liberation from all limitations are to serve the highest value, that is, truth. A person who serves the truth, and the truth that liberates humans – this is, in a nutshell, the meaning of Ives being chosen as the patron of our Festival in Stalowa Wola[9].

Ives’s patronage translated into the unique atmosphere of freedom at the Festival, which was invaluable at that time. Eugeniusz Knapik observed:

(…) I had the impression that we were constructing an enclave… Naturally, it was Krzysztof Droba who was building it, and we only became unwitting implementers of his idea[10].

Ives was present at the Festival not only through his ideas, but in the form of actual performances at the successive MMMM editions of a number of his songs and chamber pieces, which were, for the most part, Polish premieres of these works. This was a rather complicated enterprise, since Ives’s scores were unavailable in Poland and were therefore ordered via the US Consulate, which was keenly interested in promoting American music in Poland. The musicians who stood out among those who specialised in performing Ives at the Stalowa Wola Festival included Olga Szwajgier (in the songs) and the young violinist Aureli Błaszczok, PWSM student from Katowice, who played Ives’s sonatas, first with pianists Lidia Biel and Anna Lasoń, and later with Eugeniusz Knapik. The Błaszczok-Knapik duo had all the four sonatas by Ives in its repertoire and presented them, among others, during the early 1980s editions of the ‘Warsaw Autumn’. In the wake of the Ives craze, an Ives’ Songs Band was also formed, made up mostly of students from the Music Education Department of Cracow’s PWSM and led by Joanna Wnuk. The group sang and played transcripts of the songs adapted for the stage and for a vocal-instrumental ensemble[11].

The concept and its implementation

The Festival’s main aim and focus was to promote young composers whose talent and new approach to music writing in general would change the face of Polish contemporary music. Overall, however, the mission of the MMMM was to restore the alliance between composers, performers, and the audience. What is more, Droba dreamed from the start of creating an ‘interdisciplinary’ festival which would be a meeting place for artists representing different disciplines of art (the theatre, poetry, painting, etc.), as well as critics and theorists. The graphic arts were represented at the Festival mainly by Tadeusz Wiktor, Jacek Bukowski, and Piotr Kmieć (all of them from Cracow’s Academy of Fine Arts). In present-day categories, they would be described as multimedia artists, and all of them also composed music. They therefore contributed to the Festival in Stalowa Wola not only as set and graphic designers (posters, urban spatial installations), but also as composers of purely musical works and authors of music-and-graphics happenings. Especially closely related to the idea of the Festival was Piotr Kmieć’s Entering the Painting, presented during the 1st edition in 1975. The literary-musical-theatrical current was represented already at the same 1975 Festival by the Cracow-based student theatre ‘Pleonazmus’ and its spectacle Selected Scenes from Our Most Recent Decadence. In the later MMMM editions, this genre was cultivated primarily by young artists (both music school students and amateurs) as one of the numerous educational initiatives that accompanied the Festival. Both during the successive editions and on the days preceding the Festival proper, workshops were held for primary and secondary school students from the town. Of special interest were the new music workshops held by Ewa Niewalda and Józef Rychlik; there were also music theatre classes conducted by Maria Dziewulska. The effects of those workshops were always presented at the Festival, which corresponded to Ives’s profound conviction that people should “create their own symphonies” and universally express themselves through art and music. The music theatre workshops culminated in a performance of Pergolesi’s opera La serva padrona by the local youth orchestra and choir as well as soloists (PWSM students from Cracow and Katowice) during the 5th MMMM edition.

Of equal significance were events related to art criticism and debates, which gained importance with each successive edition. Starting with the 2nd MMMM, philosopher Władysław Stróżewski held Courses of Art Work Interpretation; it was in Stalowa Wola that his concept of integral aesthetics emerged, rooted in Roman Ingarden’s phenomenology. As of the 3rd edition, panel discussions were held following each day of the Festival, usually conducted by Mieczysław Tomaszewski, founding father of the Cracow music theorists’ circle. This humanist trend gained more and more popularity with each successive edition, bringing together composers (including Henryk Mikołaj Górecki, who came to Stalowa Wola as an audience member), musicologists, aestheticians, and critics of both the older and the young generation. It culminated during the 1979 edition (the last one directed by Droba) in a seminar centred around two papers then delivered: Bohdan Pociej’s Muzyka – jakiej chciałbym [The Music I Crave For] and Leszek Polony’s Nowy romantyzm [New Romanticism]. Both were important voices in the debate concerning transformations in the 1970s Polish music.

In the context of this humanist-critical aspect of the Festival, we should also mention the extensive press coverage of the event in nationwide music magazines, periodicals dedicated to the society and culture, as well as dailies, especially in local papers. There were reviews, reports, interviews, commentaries, and summaries, both during and after the Festival. The full list and presentation of these texts (both brief and longer) can be found in Ewa Woynarowska’s extensive (four-volume) diploma work (supervised by Krzysztof Droba himself[12]). It was these publications that largely decided about the public’s awareness of what was going on in Stalowa Wola – of the extraordinary and novel phenomena and tendencies which Mieczysław Tomaszewski once referred to as ‘the Stalowa Wola wave.’[13] Thanks to the young and active critics who attended the Festival events, the debut of the new and extremely interesting generation of Polish composers born in the early 1950s was soon noted and reported.

The composers: The ‘Stalowa Wola generation’

Despite all this diversity and wealth of events, the main objective of Krzysztof Droba’s ‘private initiative’ – that of promoting young composers – was not lost. On the contrary, the Festival filled a major gap, since in the circumstances of that period the young composers’ chances to win wide recognition and success were rather meagre. Droba explained:

From the start the Festival’s ambitions were rather impudent. Rather than imitating anything and benefiting from the presence of well-known names of both composers and performers, it has intended to ‘make’ new names and to impose them on other festivals[14].

Andrzej Chłopecki, a critic involved with the Festival from the beginning, wrote enthusiastically after its 1st edition in 1975:

[The Festival targets] young people who are only just beginning to reap laurels, attract audiences, and win acclaim; whose names are only now starting to appear on the concert bills and posters. For them, performing in a provincial town is not merely a sideline and a way to earn dough (yet?). They feel responsible for what they show to the ‘unsophisticated’, inexperienced audience (…), playing for which is the most difficult[15].

Krzysztof Droba personally sought out young composers and commissioned them to write works which were subsequently presented in Stalowa Wola during ‘composer-profile’ concerts. The 1st MMMM edition was dominated by women composers associated with Cracow’s PWSM. Droba recalled:

I was a rebel who emerged from under the influence of Bogusław Schaeffer and his circle. He had many interesting students, mostly (or perhaps exclusively) girls, who seemed somehow unfulfilled… Those whom I came to know better included Ewa Synowiec (an unconventional pianist and intriguing composer, then still a student), Ewa Niewalda (already a graduate and working on her experimental handbook of teaching music to children for PWM Edition)… This is why persons from this circle appeared at my first Festival, though I should immediately add that they were independent personalities and a far cry from Schaeffer’s orthodoxy[16].

Also in 1975, but already after the 1st MMMM, Krzysztof Droba met Andrzej Krzanowski, who had then freshly graduated in composition from Henryk Mikołaj Górecki’s class at Katowice’s PWSM and was performing as a concert accordionist. Krzanowski’s music made a particular impression on Droba, who heard in it “an antidote for post-serialism and dehumanised music.” Already in the following year, the premiere of Krzanowski’s Broadcast IV (also known in English as Programme IV or Audition IV, dedicated to the MMMM Festival) was given in Stalowa Wola. Other graduates from Katowice’s PWSM, Aleksander Lasoń and Eugeniusz Knapik, soon followed Krzanowski to the Festival; all the three had been born in 1951. These three composers’ activity was most closely associated with the Festival, and they were soon hailed as the ‘Stalowa Wola generation’. However, works by other composers from different regions of Poland were also presented there; among others, those by Krzysztof Szwajgier, Maciej Negrey, Anna Mikulska, Grażyna Pstrokońska-Nawratil, Zdzisław Piernik, as well as older artists: Krystyna Moszumańska-Nazar and Andrzej Nikodemowicz. Despite significant differences between the musical styles of Krzanowski, Knapik, and Lasoń, the music of all these artists came to be labelled as ‘new Romanticism’ (Andrzej Chłopecki) or ‘new humanism’ (Krzysztof Droba). 1976 is considered as the group’s symbolic debut; this was the year when Krzanowski and Lasoń first came to the MMMM (Knapik joined them at the Festival a year later). The works of ‘the three from Katowice’ were, in a way, a response to the ideas of Charles Ives which Droba had used to build the concept of his Festival. But why from Katowice? Ives’s transcendentalism seems to have harmonised in a surprising manner with notions that were central to the region of Silesia, especially with the cult of work and of the highest values, which are the aim of all human activity, including ethically-conceived artistic work that takes up weighty subjects and approaches them in a serious fashion. It was in Silesia that the unique ideal of an artist associated with Romantic-type expression, ‘singing out’ his or her message in a sincere and direct (Romantic?) manner, then took shape[17]. Nearly all these elements can also be traced in Ives’s aesthetic stance.

When talking about composers at the Festival, one must not overlook the presence of music by contemporary Lithuanian artists. Guests invited by Droba to the 3rd MMMM in 1977 included composer Vytautas Jurgutis and musicologist Vytautas Landsbergis (Lithuania’s future president). The programme of that edition included the Polish premiere of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis’s String Quartet. The 5th edition featured a concert dedicated to the output of Bronius Kutavičius. Lithuanian music was, however, much more strongly represented at Droba’s later festivals, held in Baranów Sandomierski and in Sandomierz.

An event that can be considered as the culmination of composers’ contributions to the Festival was the competition for a piece of chamber music, announced in January 1978. A jury consisting of the most eminent figures in Polish new music (Krzysztof Penderecki – chair, Zbigniew Bujarski, Zygmunt Mycielski, Marek Stachowski, Krzysztof Droba, Krzysztof Szwajgier, Mieczysław Tomaszewski, and Józef Patkowski) presented its verdict before the 5th MMMM[18]. From among the 23 submitted scores, the one which scored an unqualified victory was Corale, interludio e aria by Peleas (pseudonym of Eugeniusz Knapik). The winner himself thus recalled his participation:

I wrote Corale, interludio e aria in 1978, a year after my debut at the ‘Young Musicians to the Young City’ Festival in Stalowa Wola. The then announced competition for composers aimed to bring out in our generation’s music the composers’ artistic views on freedom, independence and originality in art. It was the time of modernism’s unfulfilled hopes and the rise of its postmodern hybrid. Few composers still followed or remembered Boulez’s famous call “not to make music out of harmony, melody, and rhythm anymore.” Today we look back at that period as a time of redefinitions and of looking for alternatives to the then official reality of [new] music. Corale, interludio e aria, written in such circumstances, reflects the spirit of the Festival in Stalowa Wola[19].

Knapik dedicated this composition to Krzysztof Droba.

The personality and charisma of the Festival’s organiser exerted a unique impact on the MMMM. This phenomenon was summed up, brilliantly and with humour, by Danuta Gwizdalanka:

Drobism is (according to the still unpublished encyclopaedia of the ‘Young Musicians to the Young City’ Festival) a direction in music characterised by high standards, artistic explorations, and the young age of composers. It is the dominant trend in south-eastern Poland, and is associated with the Festival ‘Young Musicians to the Young City’, held since 1975 in Stalowa Wola. The term has been coined from the name of the Festival’s initiator and organiser – Krzysztof Droba[20].

[1] Krzysztof Droba’s statement in Dyskusja [Discussion] [in:] Muzyczny świat Andrzeja Krzanowskiego [The Musical World of Andrzej Krzanowski], ed. J. Pater, Akademia Muzyczna w Krakowie, Kraków 2000, p. 66.

[2] K. Bilica, Młodzi Muzycy Młodemu Miastu, „Magazyn Kulturalny” 1979, nr 3, s. 45.

[3] K. Droba, O festiwalu, „Tempo Socjalistyczne” 1976, nr 8, s. 6.

[4] Miejscowe instytucje zaangażowane w organizację festiwali stalowowolskich to: Wydział Kultury Urzędu Miasta i Powiatu, Wydział Kultury, Kultury Fizycznej i Turystyki Urzędu Miejskiego w Stalowej Woli, Kombinat Przemysłowy „Huta Stalowa Wola” Państwowa Szkoła Muzyczna I st. w Stalowej Woli, Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Wojewódzkiego w Tarnobrzegu, Tarnobrzeskie Towarzystwo Muzyczne (dwie ostatnie instytucje – od czwartej edycji festiwalu).

[5] Za: Ewa Woynarowska, Festiwal niepokorny. Młodzi Muzycy Młodemu Miastu 1975-1980, Stalowa Wola 2018.

[6] Dar od losu. Krzysztof Droba w rozmowie z Kingą Kiwałą, „Teoria Muzyki. Studia, Interpretacje, Dokumentacje” 2015, nr 6, s. 132.

[7] K. Szwajgier, Komentarz w Folderze II Festiwalu „Młodzi Muzycy Młodemu Miastu”, Stalowa Wola 1976.

[8] Dar od losu…, s. 122.

[9] K. Droba, Przybliżanie muzyki: Ives, nowy romantyzm i wychowanie estetyczne, „Klucz” 2011, nr 10 [Pismo Akademii Muzycznej im. Karola Szymanowskiego w Katowicach, wydanie specjalne], s. 8.

[10] Ad origine. Eugeniusz Knapik w rozmowie z Kingą Kiwałą, „Teoria Muzyki. Studia, Interpretacje, Dokumentacje” 2015, nr 6, s. 141.

[11] Dar od losu…, s. 119.

[12] E. Woynarowska, Festiwal „Młodzi Muzycy Młodemu Miastu”. Zarys monograficzny, Akademia Muzyczna w Krakowie, Kraków 1997 [praca magisterska].

[13] Wypowiedź M. Tomaszewskiego przytoczona [w:] W. Sowa, MMMM nieco inny, „Nowiny” 1980, nr 118, s. 5.

[14] Powiedzieli. Z Krzysztofem Drobą rozmawiał Jerzy Dynia, „Prometej”, kwiecień 1979, s. 6.

[15] A. Chłopecki, Młodzi Muzycy Młodemu Miastu, „Kultura” 1975, nr 28.

[16] Dar od losu…, s. 133.

[17] Zob. K. Kossakowska-Jarosz, Śląsk znany, Śląsk nie znany: o kulturze literackiej na Górnym Śląsku przed pierwszym progiem umasowienia, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Opolskiego, Opole 1999, s. 83.

[18] Regulamin konkursu opublikowano w „Ruchu Muzycznym” 1978, nr 4.

[19] E. Knapik, Corale, interludio e aria [autokomentarz] [w:] Program 45 Festiwalu „Warszawska Jesień”, Warszawa 2002, s. 103.

[20] D. Gwizdalanka, Pro Sinfonica na Festiwalu Młodzi Muzycy Młodemu Miastu, „Pro Sinfonika III stopnia, Zeszyty Muzyczne”, 1979, nr 9.