The Polish-Lithuanian musical ties have a rich history. In different periods their intensity has been determined by various factors: by living in one political organism, or, conversely, sharing the same forms of political oppression; by geographical proximity and cultural exchange. There were also periods of cultural alienation and mutual misunderstandings, propelled by the geopolitical situation. All these elements, however, have only formed the backdrop for cultural collaboration between musicians belonging to both nations, since actual cultural events always take place on the micro-historical level, on which creative personalities and musical communities meet.

Paradoxically, it was under communism, in one of the hardest periods for both Lithuania and Poland, that extremely fruitful initiatives for cooperation were initiated. This exchange was not supported by official cultural authorities. On the contrary, it took the form of artistic collaborations between non-conformist musical milieus, and contributed to the development and growing prestige of musical cultures in both countries. Musical life in Poland (especially contemporary music festivals and publications) was in those days one of the main sources of information about the global culture for a large number of Lithuanian musicians, while in the 1970s and 80s the Polish music scene was viewed by numerous Lithuanian composers as a springboard for an international career. For Polish musicians, Lithuanian music became a source of inspiration and a topic of debates concerning art and culture. Its promotion further reinforced Poland’s metropolitan status as a cultural hub.

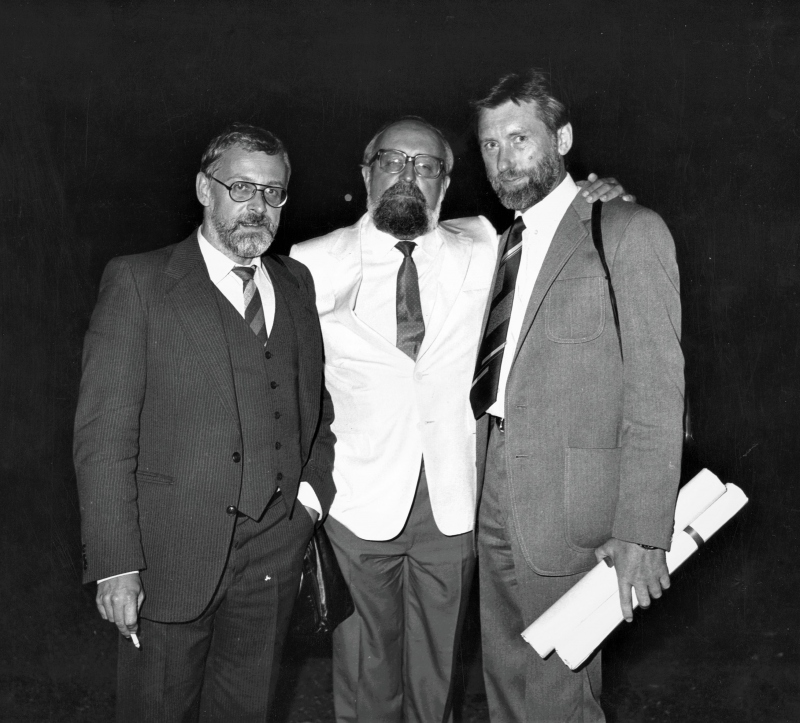

The appearance of contemporary Lithuanian music on the Polish scene was first and foremost the fruit of the consistent efforts of Krzysztof Droba. His sincere admiration for the works of Soviet-era modernists: Bronius Kutavičius, Feliksas Bajoras, and Osvaldas Balakauskas, as well as those of neo-Romantic composers who made their debuts in the 1970s, led this Polish musicologist, considered as an ambassador of Lithuanian culture, actively and effectively to take up the task of promoting and disseminating Lithuanian music on a wide scale. Droba was no less intrigued by Vytautas Bacevičius (1905–1970), the classic of Lithuanian musical modernism and brother of the composer Grażyna Bacewicz. The latter composer’s output was passed over in communist Poland. Droba’s earlier encounter with his Lithuanian colleague Vytautas Landsbergis led the Polish scholar to invite him to the 1977 Stalowa Wola festival, where Landsbergis familiarised the audience with the music of Mikołaj Konstanty Čiurlionis. These events transformed Droba’s scholarly interest into a genuine passion for Lithuanian culture. Landsbergis became the Polish critic’s guide to Lithuanian music. With time their acquaintance turned into a close friendship based on mutual trust, and thus inaugurated a new era of cultural cooperation between Lithuanian and Polish musicians.

It would be a lie to claim that Lithuanian music had been completely unknown to the Polish audience prior to the 1970s. Many, however, failed to distinguish it under the thick veil of Soviet cultural propaganda. Composer Balys Dvarionas had come to the ‘Warsaw Autumn’ as a member of the official Soviet delegation as early as in 1958; in that period he frequently guest conducted in Polish concert halls. Lithuanian composers and performers occasionally appeared in the programmes of concerts and festivals organised in Poland by the Union of Soviet Composers and by Goskontsert agency in the 1960s and 70s. Still, Droba’s generation ignored these Soviet exports. It was a generation of young non-conformist musicians who sought to establish cultural exchanges and high-quality cultural partnerships. It was in 1975 that Droba began to hold independent festivals in ‘the back of beyond’, in the small town of Stalowa Wola. Boasting rich programmes, they are considered today as the cradle of non-conformist music festivals in Poland. They were initiated and organised with immense commitment by Droba himself. What was characteristic of those events was not only their opposition to official cultural policies, but also – an openness to international culture. Importantly, the Polish musicologist resolutely included valuable works from the neighbouring countries in his festival programmes, with a particular focus on the then oppressed cultural milieus. His main criterion for selecting the music was its artistic value, based on clearly defined aesthetic and musical principles. The musical Esperanto of the second avant-garde was thus opposed and replaced by a search for a liberating and inspiring individuality in music.

On Droba’s initiative, Lithuanian music first presented at those non-conformist festivals (after Stalowa Wola there were also Krzysztof Penderecki’s private festivals at Lusławice manor, as well as those held under the patronage of the Royal Academy of Music in Sandomierz) entered the stages of the official and influential ‘Warsaw Autumn’, as well as Polish Radio programmes. What is particularly significant from the historical point of view is that all the above-listed events involved not only performances of outstanding music by Lithuanian composers active in that period, but also commissions for new works. For Lithuanian artists, limited by geopolitical circumstances, these were the first solid commissions received from foreign institutions, which allowed them to escape the limitations imposed by the official Soviet system, and to gain artistic and personal freedom. Not less importantly, Droba’s projects provided an impulse for the composition of many works which have since earned their place in the cultural memory and in repertoires, from Bronius Kutavičius’ String Quartet No. 2 ‘Metai su žiogu’ (‘A Year with the Grasshopper’, 1980) to Osvaldas Balakauskas’ Tyla. Le Silence for four voices and chamber orchestra (1986), to Onutė Narbutaitė’s Monogramme for percussion instruments (1992), and Feliksas Bajoras’s string quartet Suokos (1998).

Out of this creative partnership and opposition against the imposed political and cultural regime, another major initiative was born; namely, that of joint conferences held by Lithuanian and Polish musicologists. The first of them was notably held in 1989, a year marked by major political changes. These events were organised by the Lithuanian Composers' Union’s Musicologists’ Section together with the Department of Music Composition, Interpretation and Education at the Academy of Music in Cracow. However, their main spiritus movens was Krzysztof Droba, whose critical sense and musical intuition helped establish their form and atmosphere. The meetings went far beyond the conventions of traditional academic symposia. Their subjects were chosen in such a way as to identify problematic viewpoints and help diagnose the present-day state of culture as well as trends in its development. The same critical approach was applied to debates about tradition. Contemporary music theory was not the only area of interest. Seminars conducted by composers as well as extensive presentations of selected composers’ output were a regular feature of these conferences. They were traditionally accompanied by concerts at which new works by Lithuanian composers (Osvaldas Balakauskas, Feliksas Bajoras, Onutė Narbutaitė, Mindaugas Urbaitis) were presented on the initiative of, and as commissions from, the Polish side. Eleven such conferences were held in 1989-2010. One of their key topics was the interpretation of the history and output of the Bacevičius/Bacewicz musical family[1].

For more than 40 years, Krzysztof Droba cultivated and promoted Lithuanian music as a precious treasure. He encouraged, disseminated, shared it with others, but at the same also performed critical analyses and interpretations of that music. Dozens of his analytic articles, essays, reviews, and notes on the subject have been printed in collections of papers, conference proceedings, music periodicals, festival brochures, etc. in Poland, Germany, France, Italy, Slovakia, Lithuania, and other countries[2]. Only a small proportion of these have been published in Lithuania, but even those few had an impact on the local reception of Lithuanian music. Some of Droba’s interpretations of that music have become part and parcel of the Lithuanian musical-critical discourse. One example is Droba’s use of the term ‘neo-Romantics’ to describe the young composers of the 1970s; Lithuanians frequently interpret this notion in their own way. Droba’s musicological and critical writings follow the principle of analytic ‘polyphony’, which means that the Polish musicologist constantly returned to the sources of the same composers’ and musicians’ oeuvre, gaining new insight and testing his own observations and interpretations. It was, therefore, a kind of musicological research and music criticism whose central mission is to convey the experience of the music itself. At the same time, these writings are deeply rooted in the Polish cultural tradition with its intrinsic values and stylistic priorities. Aesthetic thought is an important aspect of identity and self-awareness. It gives meaning to the past, and attempts to grasp and describe the forms of the present, which are only just taking shape. At the same time, aesthetic reflection is a verbalisation in writing of the musical reality, on which high demands are placed with regard to style and interpretation.

Before the age of the Internet, representatives of culture were not the only ones to believe in the power of the printed word, and Aesopian language was not necessarily praised as the superior writing style. Simple words clearly telling the story of art, of human meetings, attitudes to reality, and outlooks on the world – revolutionised the Soviet public space. At this point we need to comment at least briefly on the restrictions concerning public space which became more severe in the late years of the Soviet regime. An early text by Krzysztof Droba, printed in 1984 in the Polish music magazine “Ruch Muzyczny”[3], may serve as an illustration. It comprises responses to the author’s questions given by four young Lithuanian musicians: Onutė Narbutaitė, Vidmantas Bartulis, Mindaugas Urbaitis, and Algirdas Martinaitis. According to Daiva Parulskienė (Budraitytė), this issue of “Ruch Muzyczny” disappeared from Lithuanian libraries without a trace, since directly after its publication it apparently attracted the interest of representatives of the ruling party and cultural authorities[4]. As soon as the magazine reached Vilnius State Conservatory, a meeting with a local party activist was held, to which the ‘culprits’ (that is, the young composers) were summoned. The local secretary of the Communist Party of Lithuania made derisive comments about some of their statements, such as:

“There is so much banality around, so much shallow art and entertainment, but also so much hurry and brutality. All this contributes to a sense of helplessness and pointlessness, for who could outshout such noise? And still, one feels the need to believe in something and hope for a solution. Art and music are like an island where one can listen intently to one’s own and other people’s voices. To me, they are a prayer and a link to the world.” (Onutė Narbutaitė)

Literature and poetry have been the key early impulses for my music. They taught me to feel art and recognise the spirit of my nation. During my studies at the conservatory, Messiaen, Penderecki, and Lutosławski were closer to my heart than the then dominant style of Prokofiev and Shostakovich, It was thanks to their music that I could withstand the prevailing dry and technical approach. Looking back from a distance I can see that what retains significance is the music of Arvo Pärt, the poetry of Mandelstam, and the paintings by Wróbel… I’d like my music to be modest, less external, and more intimate. I’m afraid that with its rustic soul it [my music] may get under the wheels of a train, or be distracted by the skyscrapers.” (Algirdas Martinaitis)

The composers were accused of individualism and disloyalty, of espousing unacceptable ideals and priorities. From the historical perspective, these paradoxical events that took place more than three decades ago prove that ideologisation of cultural conflicts focused not on maintaining the Soviet cultural doctrine, but on controlling the public space. The increased limitation of public space in the late Soviet era (i.e. the early 1980s) has attracted the attention of many historians of the USSR to the paradoxical relation between its political authorities and the society. Slavoj Žižek, who studied the ideological transformations in the Soviet Union, describes the efforts at public space regulation undertaken in that period as the result of the rulers’ paranoid belief in the power of the word. The authorities’ reaction to every manifestation of public criticism was nervous to the point of suggesting a panic. The philosopher, however, describes this period as a time when cynical ideology prospered, and when social activists viewed the official values cynically and with a distance. The government assumed an attitude of relative tolerance to the society’s domestic attitudes in an attempt to uphold the legitimacy of its power. In contrast, Lithuanian historians and sociologists such as Arūnas Streikus and Vylius Leonavičius, who examined other aspects of the Soviet system as a paradoxical type of modern society, attribute the ideological tensions to the authorities’ failure to secure legitimisation. They also point to the fact that the government’s attempts to maintain full institutional control clashed with the society’s distrust and with the emancipatory longings of individuals. In representatives of the party and of the bureaucratic establishment, the said short publication provoked anxious questions concerning the unity of political aims in Polish-Soviet relations. The anti-communist ‘Solidarity’ movement, as well as the activity of Pope John Paul II and the tensions following the introduction of military regime in Poland (1981–1983) – all these factors made the authorities particularly alert to all forms of informal contacts with Polish musicians and Poland’s cultural circles. This is why the Soviet rulers hindered the performances of Lithuanian music in the 80s Poland, even though no sanctions were imposed against the same composers’ works being presented at festivals in France or the official congress of the Union of Soviet Composers in 1987.

The political impact of Droba’s publications and of his broad culture-building activity, including specific reactions of the authorities (he obtained permission to visit Lithuania only three times before 1989), deserves a more detailed historical study. The Polish musicologist’s interviews and conversations with Vytautas Landsbergis were frequently printed in the press in Lithuania, elsewhere in the Soviet Union, as well as in Poland, especially in the period of political transformations. The effect of those publications was not only political, but also social and cultural. They generated a wider interest in Lithuanian music in the Polish artistic circles, led to commissions for new works from Lithuanian composers, inspired television and radio broadcasts as well as other cultural initiatives in a period of great importance to Lithuania, which strove to obtain international recognition and to open to the world. Droba was always an advocate of in-depth dialogue, which confronted various horizons of experience. His support for Lithuanian music made the Polish audience aware of a luminous gallery of Lithuanian musicians, initiating and documenting changes in the perception of that music in Poland as well as the unique and most likely unrepeatable period when artistic and personal friendships flourished in spite of ideological restrictions and political turmoil.

[1] On Droba’s initiative, copies of Vytautas Bacevičius’ correspondence with his family in Poland (more than 1600 letters written in 1945–1970) were transferred in 1995 to the Lithuanian Archives of Literature and Art (Lietuvos literatūros ir meno archyvas) in Vilnius.

[2] A more extensive though still incomplete bibliography of Krzysztof Droba’s writings can be found on the website of Polish Music Information Centre (patrz www.polmic.pl).

[3] Młoda muzyka litewska [Young Music in Lithuania], “Ruch Muzyczny” 1984 No. 19 [editor’s note].

[4] Daiva Budraitytė, Młoda muzyka litewska w latach osiemdziesiątych – i później [Young Lithuanian Music in the 1980s and Beyond]. In: W kręgu muzyki litewskiej. Rozprawy, szkice i materiały [Around Lithuanian Music. Theses, Sketches, and Materials], ed. Krzysztof Droba, Kraków 1997, p. 110.